The Two-Minute Guide to Current Expected Credit Losses

Banks and other financial companies with significant credit exposure have been worrying about Current Expected Credit Losses (CECL) since its announcement in 2016. Now companies with lesser exposures are finally coming to the table, having realized that calculations, policies, methodologies, and procedures will need to be developed to deal with this fast-approaching accounting change. In this blog post, we’ll review key features of the CECL standard and take a look at what companies will need to do to be ready.

What is CECL?

CECL is one of the primary pieces of the new ASC 326, Financial Instruments – Credit Losses, introduced in ASU 2016-13 and modified with ASU 2018-09. This rule, effective for fiscal years beginning after December 15, 2019 for SEC filers and a year later for non-SEC filers, requires companies to adjust the value of any debt securities held at amortized cost for their expected credit loss.

I thought we already wrote down credit losses, what’s different?

In the past, allowance for loan and lease losses was applied only as debts became delinquent or otherwise were actually expected not to be paid, referred to as the loss discovery period. Under the new standard, an allowance is considered as part of the value on day one. So if a sale is made with a 90-day payment term, the payment is recognized net of an expected loss. Over time, this loss is adjusted based on the actual receipts and losses that the company incurs.

By applying this standard, the hope is for a smoother recognition pattern for the revenues — because losses are accumulated as they are expected — rather than based on singular triggering events.

Isn’t CECL just for banks?

CECL is defined by the instruments it covers, not the type of institution. It covers all financial instruments held at amortized cost, which includes a large range of debt securities. With that said, many of these instruments — such as loans held for investment, net investment in leases, and standby letters of credits — are primarily (if not exclusively) the purview of financial institutions.

Some of the most common items of concern held by non-financial institutions are trade receivables, lease receivables, and held-to-maturity debt securities. Others include contract assets, lease receivables, financial guarantees, loans, and loan commitments. Under the new guidance, these securities will need to have losses forecasts and applied to the balance.

With that said, banks will find CECL applies to a significant portion of their balance sheet covering a wide range of instruments, while non-financial companies may be limited to 90-day receivables for purchases invoiced upon delivery. The collective impact of a shorter term and fewer covered instruments is a smaller discount on a relatively lower number for these non-financial companies. As a result, many companies may find the CECL adjustment to be relatively small compared to their overall operations, while banks have been preparing for years for this eventuality.

How do I estimate my CECL?

Companies are expected to start with their historical experience in estimating their credit losses. For example, a company which has historically experienced charge-offs of 2% of their billings might reasonably start with 2%. As time goes on, and uncollected accounts become more likely not to pay, they may increase this estimate for remaining billings — again, based on the historical experience for slow payers and/or delinquent accounts.

Importantly, however, the rule also requires considering qualitative factors about the company, the borrower, and even the broader economy. For example:

- A company that has recently sold many products to new companies without a payment track record may wish to increase the loss rates on these untested borrowers.

- If a borrower’s business appears to be in trouble, perhaps reflected by smaller order sizes or declining stock prices, this may indicate financial distress and a potentially higher loss rate.

- Companies that believe a recession is imminent may increase their loss rates.

We note that qualitative factors can be particularly difficult to validate, so we expect to see diversity in practice for some time as people implement this new standard.

What should I be thinking about for my data analysis?

Modeling credit losses falls into a class of analysis referred to as hazard models. Hazard models look to understand when and why items leave a group, and despite their name, don’t just look at bad things. Those who work with ASC718 will recognize that forfeiture and exercise rates are both covered by hazard analysis. In this case, we have two events, a debt that can either be repaid or be deemed a loss.

What’s important is to group receivables in reasonable ways. For example, when estimating probable losses in the past, we’ve considered the following:

- Total term of the contract

- Remaining term

- Creditworthiness of the borrower

- Past payment experience from the borrower and similar borrowers

- Whether this is part of a continued business relationship or a one-off

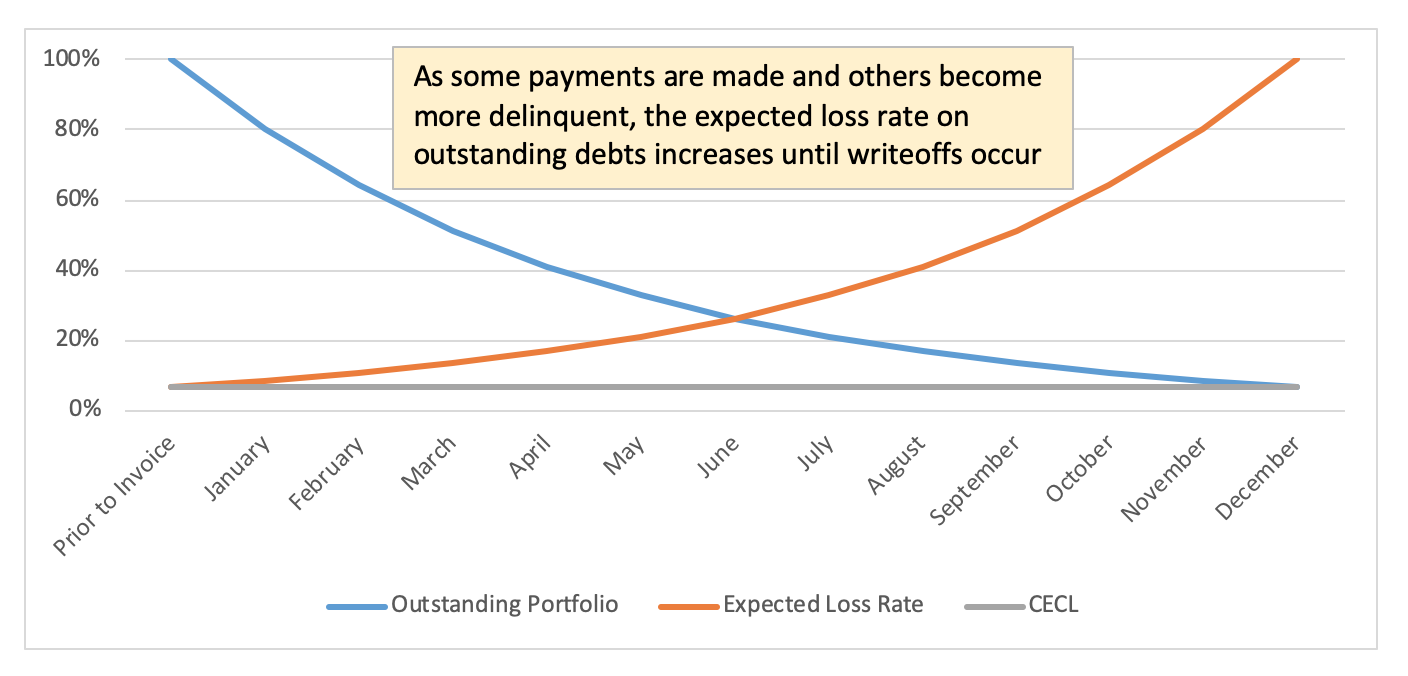

For trade receivables, we expect that the overall value of the receivables goes down over time, but the rate of loss goes up. For a company with perfect predictions, the actual loss for a given set of receivables should remain constant. The following graph shows how this holds for a payment receiving 20% of outstanding receivables a month for year, with a loss of 7%.

How should I be thinking about my analysis?

First, assess the assets covered and the size of the impact. Consider the size, term, and historical loss rates for instruments covered by CECL. Understand the current impairment model and the assessments that are used. If the loss rate moved by a few percent, what would be the impact? Based on the size of the impact, the depth of your analysis may be affected significantly.

Second, it’s important that analyses, especially subjective components of them, are based on well-documented and reasonable principles. They should also produce results consistent with expectations. If you haven’t developed a model yet, now is a good time to do that and consider the key factors you wish to use. If your company has developed a model, consider:

- Running sample calculations

- Stress-testing the model

- Making sure that the model results are reasonable (even if there are significant changes to the underlying assumptions)

- Drafting sample disclosures

Also, for data analysis, consider the lookback period and whether any time period has a significant impact on the analysis. If it does, you’ll need to decide whether this period should be included, weighted differently, or excluded.

In short, with the first CECL report around the corner, companies who have been putting this on the back burner should be working right now to get their model together for a smooth transition.

What if I have more questions?

For any questions about CECL, please don’t hesitate to contact me.